How do you like Auschwitz?

"How do you like Auschwitz?" the Chief Commander of the Political Office of Auschwitz asked Laura Rusk, the 22-year-old blue-eyed blonde standing in front of him in the central interrogation unit of the camp.

Stunned by this surprising and dramatically humorous question, Laura knew immediately that her life depended on her answer.

She looked the Commander straight in the eyes and boldly answered in fluent German: "I can't complain."

The Commander burst out laughing: "So we share the same opinion – I think that every healthy person can live a hundred years in Auschwitz." He was pleased with her answer. Laura was released and sent back to the barracks. She understood that her good judgment had spared her, but for how long?

Laura recently moved to Beth Protea, on a trial-period she insists, as she feels that as long as she is capable of traveling and testifying about what she had witnessed and the miraculous way she had survived WWII, her duty is to continue to share and transmit, together with other survivors of her generation whose voices are slowly fading away. But hers is still a very powerful one.

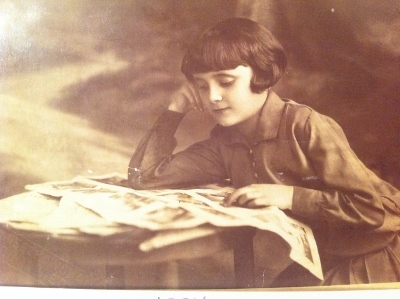

Laura's life is an endless adventure, from Poland, her birthplace in 1922, till today at the Beth Protea. Laura has been traveling and testifying throughout Germany, Switzerland, France and the USA. Her testimony is recorded in the archives of Yad Vashem, on DVD, on print and on the Internet.

She was born in Silesia, in southwest Poland, and raised by a prosperous aunt and uncle, as her mother was always working and her father served in the Polish army.

She suffered being apart from her parents and siblings, whom she visited often, but life took its course without giving her a say in the matter. In return, she received an excellent bilingual education, which together with her looks, self-pride, luck and divine intervention, saved her life.

In 1939, as she was making plans to begin university at the Sorbonne in Paris, WWII broke out.

Overnight, Jewish life was utterly disrupted. Everyday was a struggle for survival, with no guarantee of seeing loved-ones at night. People lived in permanent shock. Hunger, humiliation and public hangings became daily routine.

This horror lasted until 1942 when everyone was summoned to the football stadium. Every soul was present; the sick, the fit, the elderly, as well as mothers with their newborns.

Everyone stood in the rain for 24 hours until the selection started. A Gestapo chief stood facing a crowd of thousands, pointing to each person to go the left or to the right.

The young and healthy were sent to one side; the elderly and mothers with younglings were forced to the other. Standing in the young and healthy group, Laura's eyes were searching for her family, but they were nowhere to be seen.

Reacting rapidly, she attached herself to a Red Cross delegation, which protected her temporarily from deportation, as most of the young men and women were being loaded onto trucks.

Shortly after, she witnessed the deportation of hundreds, walking towards the train station. Among them, she suddenly saw her entire family (other than the men): her mother, young siblings, grandparents, cousins, and aunts – 40 of her loved-ones. Unbeknownst to her, this would be the last time she would see them as they were loaded onto the trains and disappeared forever.

A few days later, Laura was stopped and sent away with other young women to Peterswaldau, an old rundown fortress turned ammunition work camp.

The women slaved day-and-night at the factory, while being under-nourished and without warm clothes to withstand the cold winters. This is where she decided to take her destiny into her own hands.

She planned her escape for the following Sunday, before the dawn roll call. She stuffed her bed with blankets and ran down the stairs, across the yard, in the direction of the barbed wire that surrounded the camp.

As she was about to cross, with one leg already over, she saw two SS soldiers walking in her direction. Paralyzed she waited and remained silent as they called: "Is anyone there?" After two interminable minutes, they eventually headed back into the building.

She climbed over the seemingly insurmountable walls of the fortress and jumped to the other side. She was finally free.

Unfortunately, her freedom was short-lived. When she was denounced and brought to the Gestapo in a nearby town, she knew that the gallows were awaiting her.

To her surprise, the miraculous interrogation did not pan out as expected, turning into a job offer as a Polish-German interpreter instead. But her situation remained precarious as she awaited her new work documents impatiently.

Her relief was yet again short-lived. Word of her escape had reached the nearby villages and she was soon back in the interrogation room.

This time she decided to confess and was offered a choice – either back to Peterswaldau and face the gallows, or immediate death by gasification at Auschwitz. She chose Auschwitz – a decision that saved her life! Laura arrived to Auschwitz in the middle of the night. When the train-doors opened, she was blinded by strong lights and deafened by the barking of dozens of dogs.

The prisoners were lined up and marched for several kilometers towards the flaming site of Birkenau, where the gas chambers were located. The air was heavy with ash and the unshakable stench of burnt flesh. She was taken to a barrack where she was given striped clothes.

Her hair was cut short, although she refused to have it shaved, and she received a tattoo on her left arm. 79564 would be her new identity. From a corner window, she witnessed the nightmare unfold before her eyes.

Hundreds of people were being shoved towards a building from where ash was slowly ascending and then floated effortlessly all around.

It was now her turn to be among the crowd marching towards the shower building, when suddenly, over loudspeaker, 79564 was called out. Two soldiers pushed their way through and pulled her out of the advancing crowd.

The tattoo had just saved her life. Because she had arrived with a registered political prisoners transport, she could not be disposed of without a trace like all the other poor souls. But death at Auschwitz was a question of when - not if - as she remained in fear of what was yet to come.

A few days later, two SS men brought her to Auschwitz' Commander of the Political Office, the highest instance over life and death. Terrified, she thought about the death sentence for having fled Peterswaldau. The interrogation did not last very long. She was asked who had helped her escape and how it was possible to flee from such a well-guarded concentration camp. The Commander must have been impressed by her courage and the way she described her escape. The interrogation ended with the Commander's simple question: "How do you like Auschwitz?"

Laura wondered whether this cynical question was asked out of curiosity, or if it was a very incomprehensible joke. Her answer could mean the difference between life and death, as she calmly replied: "I can't complain."

He laughed and retorted: "So we share the same opinion – I think that every healthy person can live a hundred years in Auschwitz."

During these terrible trials, Laura always conserved her humanity. One day she found a potato. She waited until everyone had gone and soaked it in the leftovers of that night's meal.

She nursed her treasure until it felt soft and took it back to her shared bunker. Just as she was about to eat it, she felt starving eyes staring at her. She knew that she had to share it. Despite all the horror – her caring nature remained unwavering.

Laura describes Auschwitz as a unique phenomenon in the history of mankind - an industrialized genocide that defies human reason and cannot be defined nor understood.

Seventy years later, the contemporary generation is responsible for learning from history's lessons and continuing the fight against racial and religious discrimination. It has to bear this responsibility, so that what happened never happens again.

■Written by Laura Rusk, with the help of her loving family (two daughters, five grandsons and nine great grandchildren).

Contact: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Comments